Designer Diaries: Tropicalia and Sinister Institute, or Two Games Nineteen Years in the Making!

I was fortunate to have two new games launch at SPIEL Essen 25: Tropicalia and Sinister Institute. Both of these games have long development histories — eleven and eight years respectively! — and I learned a lot from designing both. I hope you enjoy the stories of how they came to be!

The story of designing Tropicalia begins over ten years ago. It was 2014, and I was thinking a lot about worker placement. The initial flurry of worker placement games had died down a bit (oh, the heady days of 2007-2011!), and then Lords of Waterdeep felt like a distilling of what everyone loved about the mechanism, or maybe a summation of the first five years of this exciting trend. I was wondering whether there was anything new I could do with worker placement, and if so, whether it might have a place in one of my designs.

One day, something extremely rare happened: I had a design idea that arrived fully formed in my head — and also worked well from the first test! This almost never happens to me, and I am super envious when I hear other designers talk about such epiphanies.

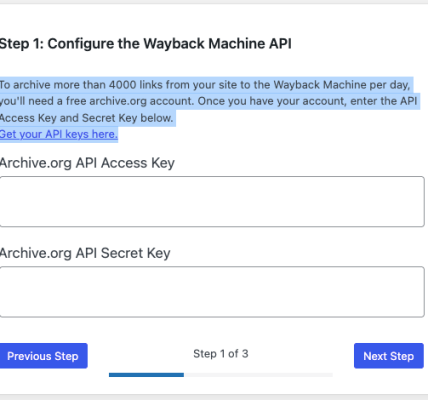

Here’s the idea: There’s a grid of worker-placement action spaces. The players take turns placing all their workers around the edges of the grid, one at a time at the end of a row or a column. Then the players take turns moving one of their workers along its row or column to claim the space they wish to activate. In short, the worker placement has two phases: first claim rows and columns, then claim spaces in those rows and columns. This system created an exciting little puzzle of tactical timing, and I was surprised how well it worked from the start. However, after such an easy beginning, it would take me almost another decade for the rest of the game to be completed. Such is the process of game design!

A diagram explaining the two-stage worker placement from the Tropicalia rules

The grid-based worker-placement system felt like a solid central mechanism for a game…but my next step was to figure out what the actual aim of the game was, or in other words, what sort of actions the spaces would grant to the players.

I tried a few ideas and discovered that collecting resources in some spaces, then selling them in others created interesting timing decisions for the players. You had to order and prioritize when you collected and when you sold. Some nice tense questions began to arise: Which column should I claim before someone else does? How urgent is it that I claim that space in my row before an opponent claims it from their column? Should I rush to sell these for $3 each now, or should I collect a few more but maybe sell them for only $2 each later?

I worked on the game for a few months and decided on a 1920s gangster theme. The grid of spaces became city blocks, and the workers were gangsters picking up different types of booze to sell at speakeasies.

When I was happy with the design, I decided to submit it to game design competitions. Earlier in my design career, these competitions were a fantastic way for my designs to get exposure, and for me to get feedback from people in the industry. I was really glad to be one of the four games recognized in the 2015 Boulogne-Billancourt Concours International de Créateurs de Jeux de Société. This even led to publisher interest! So I thought “Chicago” was on its way to release.

The prototype of the first version, named “Chicago”

A little while later the publisher decided to pass on the game and returned it to me, so I decided to put the project aside. The design felt resolved and complete, but I think I also knew it was missing that extra spark which makes a good game special.

Over the next while, I considered reworking the design to be even simpler. Perhaps my worker-placement system could be employed in a more stripped-down game, maybe even a simple card game. After all, one of my main design interests is taking one mechanism and trying to build a simple game around it. Unfortunately, the results weren’t great, and I felt that the extra elements in the original game needed to be there to hold the player’s interest. Still, the feeling that the game could be improved persisted.

I later tried the opposite approach — making the game more complex. For most designers, I think it can be quite a natural move to add a new system or layer of decisions onto an existing game, but this is something I so rarely do that I found it a real challenge! My usual instinct is to take elements away to showcase one simple system, not to bolt systems together.

And I kept thinking to myself that the grid-based worker-placement system was really solid, so why clutter it with other things?

Around 2017, I began working on the design again and re-themed it to a tropical island, which felt brighter and more inviting. Now you were landing your workers on the beach around the island in the first phase, then moving them onto the island in the second.

My first attempt at adding something to the core system was to bring in a sort of connections mini-game. Now when you made money from selling goods, there was an extra step to convert money into points. You had to spend money to build statues at intersection points on the island grid. You would score points for having clusters of statues connected along grid lines, racing your opponents to build in the best spots. This worked okay, but I could tell it was not engaging enough to be the answer. However, working on this version slowly convinced me that my worker-placement mechanism wasn’t fully satisfying all by itself. Using it to “power” another system was feeling more and more like the right direction to head in.

The first version of Tropicalia that included the statue-placement mechanism

I soon decided to go all-in and try bringing a substantial new system into the game. I love tile-laying games, but hadn’t done something with old-fashioned square tiles since Cacao, so on a whim I decided to try a new system in which players build their own village with different tiles they have purchased. The main shared island is where you make money, but building on your personal island is how you score points. Village tiles are purchased from a sliding market, and these tiles do different things when placed: some just give points, some require set collection, some have to do with adjacencies in your village, and others play into the worker-placement system by providing you with new ways to gain goods.

In a sense, I was mashing two games together: my worker-placement game, and this tile-placement village-building game. For a little while, I felt uncomfortable about this, almost like I was breaking one of my own game design maxims or doing something really “inelegant” to make the game work — but looking back, I was just accepting that while some simple systems may be able to carry an entire game, others cannot. Some systems are best employed as one challenge intertwined with other interesting gameplay elements. Again, this is nothing out of the ordinary for most designers, but for me it was a real adjustment!

Does this make Tropicalia my most complex game? Not really. Gizmos still has many more unique elements to consider and combine, and Llamaland is more of a brain burn, yet Tropicalia does stand out to me among my own designs because of its design story and how it features two quite distinct systems.

Once I began showing the prototype again, Mojito Studios showed an interest in the game, and I was so glad about their decision to bring Naïade on board to illustrate it! He is one of my favorite board game artists and the sunny and friendly final art is more or less exactly what I was hoping for when I made my prototype! For fans of family-weight worker-placement and tile-laying games, I hope you will enjoy your visit to Tropicalia!

•••

For a long time I’ve kept a list of game ideas that one day I’d like to take a crack at. The ideas on this list are usually pretty vague, concepts that excite me but I’m not sure how I’d tackle them. Sinister Institute began when in 2017 I started work on an idea from this list that I simply called “Adventure”. Like Tropicalia, this game took a long time to come to fruition and spent time with different publishers, but I think what is most interesting about its story is its beginning.

What was “Adventure”? It was a game with exploration, questing, monsters, mazes, and magic items — not a full-on RPG, but something that evoked playing Adventure on the Atari 2600 or The Legend of Zelda on the NES.

Another project that has allowed me to step into this genre is the Adventure Games series I created with Mathew Dunstan and KOSMOS. Especially in the first box, The Dungeon, I got to explore the narrative side of an adventure game as this series is story-focused with lots of text to read as you make your way through the scenario — but this game would focus on an adventure not so much as a narrative, but as a puzzle to be solved.

Adventure on the Atari 2600

Usually when I begin a design project, I think a lot about the end product. I give myself some sort of design brief and try to lock in initial ideas about the audience, components, game length, and so on.

In this case, though, I wasn’t sure where the game would land in most of these areas. All I had was a genre — even less, the “vibe” of a Zelda-like adventure game — so I proceeded by letting some of the tropes of the genre guide me and act as starting points. The first element I was sure would be in the game was map tiles. I knew the game needed a feeling of exploration and that players should be revealing the world tile by tile and finding various paths to follow, so I started drawing all sorts of possible map tiles in a notebook, experimenting with how different pathways would work, turning and intersecting with each other across tiles.

Some early notes where I was experimenting with map tile design.

One inspiration here was Tsuro as I have always loved how this game’s tiles are almost a design lesson in how four different paths on a square tile can behave. Although I have never played Magic Realm, the map tiles in it have always fascinated me. Their intricate design means that every different layout creates unique maps.

The map tiles in Magic Realm (Image: @jardeon)

As I was prototyping cardboard tiles, I realized that it was kind of interesting to lay them out in a grid, then rotate one of them. New pathways would open up, and others would close off in dead ends. This seemed like a good central idea for the map traversal in the game; the players move around on the tiles, but can also rotate them to forge new paths ahead. This meant I could keep the world physically reasonably small, but still create the feeling of a puzzly labyrinth.

Next, I knew the game should have quests in it. Not being sure what they would be mechanically yet, I started brainstorming descriptions of different things that could be exciting challenges in this simple fantasy world: returning a lost crown to the king, helping out an old hermit who needs medicine, finding a long lost treasure, and so on.

A pattern I saw with most of these ideas is that they usually required finding something, then taking it somewhere — and this suggested some sort of “pick up and deliver” system. I already knew that as the players explored the world they would find item tiles around the map that would give them special actions, so I decided to introduce a bunch of treasures into the item tile deck, objects that don’t give you an action, but have a role to play in the possible quests that come up.

For me, pick up and deliver can sometimes feel a bit repetitive as a central mechanism in a game, but I wondered whether the game being co-operative might add some interest. The players could pick up items for each other, take them somewhere on another’s behalf, exchange them, and so on. This would also create a lot of opportunity for planning and discussion as a team around the table.

Now I had the central structure of the game, and a goal for the players — work together to complete quests before…before what?

How the map tiles looked in later prototypes

The next step was to figure out what was bad about this world: What was getting in the way of the players completing quests? The first most obvious answer was time. As in many co-op games, I thought that the players working against a game timer would create good tension, but surely in an adventure game we also need an enemy, a big boss to fight. And of course in homage to Adventure on the Atari 2600, it had to be a dragon! A dragon could fly around the map and attack the players. It could also set fire to certain tiles, forcing the players to either deal with the flames or find a new way to get where they needed to go.

To make all this work together, I created the event deck. Every turn, an event card is flipped and it determines how the dragon behaves — and when the deck is exhausted, you have run out of time. This made sense, but now I had this whole deck of cards just to move a dragon around, so what else could this deck do? I had another brainstorm about interesting little stories that might occur in this world, various happenings that could be expressed on these cards: a wandering healer offers you help, a magical rain comes to put out fires, or a friendly dove transports one of your items to another player elsewhere on the map. I renamed this deck “story cards”, and now the heart of design was starting to come together.

Early examples of story cards

If all of this is sounding pretty “generic fantasy”, that’s because it was! Not being too sure exactly which way I would go with the theming, I purposely kept everything as vanilla as possible for most of the design process. The name of the prototype progressed from “Adventure” to the only slightly more specific “Story Quest”!

It wasn’t until Mojito Studios took an interest in the game that I started to think more seriously about the actual theme, but in the end it was the team at Mojito who came up with the world of Sinister Institute. Instead of the setting being a castle and a forest, we are now students at a magical college deep in a haunted swampland. The dragon is now a top-hatted evil sorcerer, and the fire has become his ghostly minions. Instead of quests being side stories that give you victory points, they are now rituals performed with certain ingredients that are direct attacks on the sorcerer.

This theme may sound pretty Potter-esque, but to me when I look at the finished product it feels more like Tim Burton making a Jonathan Strange spin-off for teenagers…if you can imagine that! So much of this flavor comes through in Edu Valls‘ amazing illustrations, which are filled with great spooky little details.

A closer look at a swamp and school tile

So where my “Adventure” project ended up is a family-weight co-op adventure game with a cool creepy setting. What I enjoy most about Sinister Institute is its balance between individual player agency and working together as a team. Often the players will be spread out across the swamp working on their own thing, but there are still ways to help each other, discuss future plans, then set them in motion.

We also managed to get a whole lot of variability into the game, with many elements changing each play: the map layout, where the items turn up, the story cards that are in the deck, and the eight characters who each have a special ability that they can level up. For young-at-heart game groups who want to go on a spooky adventure together, I really hope you will enjoy exploring the world of Sinister Institute!

Thanks so much for reading!

/pic8399191.png)

/pic9144959.jpg)

/pic9144973.jpg)

/pic9144979.jpg)

/pic9210800.png)

/pic8035215.jpg)

/pic9145186.jpg)

/pic9145019.jpg)

/pic1632481.jpg)

/pic9145020.jpg)

/pic9145021.jpg)

/pic9099756.jpg)

/pic9210801.png)